In the 12th century and afterwards mutual raids involving Lithuanian and Polish forces were sporadically taking place, but the two countries were separated by the lands of the Yotvingians. The late 12th century brought German settlers to the mouth of the Daugava River area. Military confrontations with Lithuanians followed at that time and at the turn of the century, but for now the Lithuanians had the upper hand.

From the late 12th century an organized Lithuanian military force existed; it was used for external raids, plundering and gathering of slaves. Such military and wealth-acquiring activities and the attendant social differentiation triggered a struggle for power in Lithuania, which initiated the formation of early statehood, from which the Grand Duchy of Lithuania developed.

In 1219, twenty-one Lithuanian chiefs signed a peace treaty with Galicia–Volhynia. This event is widely accepted as the first proof that the Baltic tribes were uniting and consolidating.

From the early 13th century, two German religious orders, the Livonian Brothers of the Sword and the Teutonic Knights, became established in the region. Under the pretense of converting the population to Christianity they conquered much of the area that is now Latvia and Estonia, in addition to parts of Lithuania. In response, a number of small Baltic tribal groups united under the rule of Mindaugas. Mindaugas, originally a kunigas or major chief, one of the five senior dukes listed in the 1219 treaty, is referred to as the ruler of all Lithuania as of 1236 in the Livonian Rhymed Chronicle. Mindaugas conquered the Black Ruthenia region (the vicinity of Grodno, Brest and Navahrudak).

Pope Innocent IV's bull regarding Lithuania's

placement under the jurisdiction of the Bishop of Rome, Mindaugas' baptism and

coronation

Around 1240 Mindaugas ruled over all of Aukštaitija and was in process of extending his control to other areas, killing rivals or sending relatives and members of rival clans east to Ruthenia so they could conquer and settle there. They did that, but also rebelled and the Ruthenian duke Daniel of Galicia sensed an occasion to recover Black Ruthenia and organized in 1249-50 a powerful anti-Mindaugas (and "anti-pagan") coalition, which also included Mindaugas' rivals, Yotvingians, Samogitians and the Livonian Teutonic Knights. Hovewer, Mindaugas' brilliant moves took advantage of the contradictions within the coalition he faced.

In 1250 Mindaugas entered into an agreement with the Teutonic Order; he consented to receive baptism (the act took place in 1251) and relinquish his claim over some lands in western Lithuania, for which he was to receive a crown in return. Mindaugas was then able to withstand a military assault (1251) from the remaining coalition, and, supported by the Knights, emerge as a victor and confirm his rule over Lithuania.

On July 17, 1251, Pope Innocent IV signed two papal bulls, ordering the Bishop of Chełmno to crown Mindaugas as King of Lithuania, appoint a bishop for Lithuania, and build a cathedral. In 1253, Mindaugas was crowned and the Kingdom of Lithuania was established, for the first and only time in Lithuanian history. Mindaugas "granted" parts of Yotvingia and Samogitia that he did not control to the Knights in 1253-1259. A peace with Daniel of Galicia (1254) was cemented by a marriage deal involving Mindaugas' daughter and Daniel's son Shvarn. The rival nephew Tautvilas returned to his Duchy of Polotsk and Samogitia separated, soon to be ruled by another nephew Treniota.

In 1260 Samogitians, victorious over the Teutonic Knights in the Battle of Durbe, agreed to submit themselves to Mindaugas' rule on the condition that he abandons the Christian religion; the King complied by terminating the emergent conversion of his country, renewed anti-Teutonic warfare and expanded further his Ruthenian holdings. Mindaugas thus established the basic tenets of medieval Lithuanian policy: defense against the German order expansion from the west and north, conquest of Ruthenia in the south and east.

Pagan Lithuania was a target of Christian crusades of the Teutonic Knights and the Livonian Order. In 1241, 1259 and 1275 Lithuania was ravaged by raids from the Golden Horde, which earlier (1237-1240) debilitated Kievan Rus', the country that had already suffered from its 12th century divisions. After Traidenis' death, the German Knights finalized their conquests of Baltic tribes and they could concentrate on Lithuania, especially on Samogitia, to connect the two branches of the Order. In particular, in 1274 the Great Prussian Rebellion ended, and the Teutonic Knights proceeded to conquer other Baltic tribes, including the Yotvingians in 1283; the Livonian Order completed its conquest of Semigalia, the last Baltic ally of Lithuania, in 1291.

Gediminids and Lithuania's great expansion[edit]

The House of Gediminas began with Butigeidis and his brother Butvydas, who ruled 1292-1294. Butvydas' sons, the brothers Vytenis (1295-1315) and Gediminas (1315-1341), after whom the Gediminid dynasty is named, had to deal with the increased Teutonic pressure, bloody and costly raids and incursions. Grand Duke Gediminas was the first of the leaders responsible for Lithuania's state power and the great expansion into Ruthenia.[4][24]Gediminas and his people were pagan, but the ruler kept contacts with the world of Western Christianity, including Western Europe. Casimir, the son of the Polish king Władysław, married Gediminas' daughter Aldona, the future queen of Poland. A defensive alliance with Poland was concluded in 1325.[4]

Of Gediminas' seven successor sons, four remained pagan and three became Orthodox Christians. From 1345 Algirdas took over as the grand duke. He in practice ruled Lithuanian Ruthenia, while Lithuania proper was the domain of his equally able brother Kęstutis. Algirdas fought the Golden Horde Tatars and the Principality of Moscow, Kęstutis took upon himself the demanding struggle with the Teutonic Order.[4]

Algirdas died in 1377 and his son Jogaila became grand duke when Kęstutis was still alive. Jogaila made overtures to the Teutonic Order and concluded a treaty with them in 1380, contrary to Kęstutis' principles and interests. Kęstutis felt he could no longer support his nephew, attempted to remove him from the throne and a civil war (1381–1384) ensued. Kęstutis was captured and died in Jogaila's custody, but his son Vytautas escaped.[4][25]

Jogaila agreed to the Treaty of Dubysa with the Order in 1382, an indication of his weakness. A four-year truce stipulated Jogaila's conversion to Catholicism and the cession of half of Samogitia to the Teutonic Knights. Vytautas went to Prussia seeking support of the Knights for his claims, including the Duchy of Trakai, which he considered inherited from his father. Jogaila's refusal to submit to his cousin's and the Knights' demands resulted in their joint invasion of Lithuania in 1383. Vytautas, however, having failed to gain the entire Duchy, decided to establish contacts with the Grand Duke. Upon receiving from him the Grodno, Podlachia and Brest areas Vytautas switched sides in 1384, destroying the border strongholds entrusted to him by the Order. The two Lithuanian dukes acting together waged in 1384 a successful expedition against the Teutonic ruled lands.

By that time, for the sake of its long-term survival, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania had initiated the processes leading to its imminent joining the European Christendom.

14th century Lithuanian society

Towns developed to a much lesser degree than in nearby Prussia or Livonia. Outside of Ruthenia, the only cities were Vilnius (Gediminas' capital),[20] Trakai and Kaunas. Vilnius in the 14th century became a major trade center, linking Eastern Europe with the Baltic zone. Of the passing Ruthenian, German and Polish merchants, many settled there. Lithuanian (from the late 13th century) and foreign currencies were widely used.

The state had a patrimonial structure of power. The Gediminid rule was hereditary, but the ruler would choose the son he considered most able to be his successor. Councils existed, but could only advise the duke. The huge state was divided into a hierarchy of territorial units, administered by designated officials, who were also empowered in judicial and military matters.

Lithuania, not an officially Christian state, was an anomaly in Europe and had no allies. This situation was becoming increasingly untenable in the 1380s.

Introduction of Christianity, dynastic union with Poland

Jogaila and Vytautas

The Catholic influence and contacts, including German settlers and traders, had also been increasing for some time around the northwest region of the empire, Lithuania proper. The Franciscan and Dominican monk orders existed in Vilnius from the time of Gediminas. Kęstutis in 1349 and Algirdas in 1358 negotiated Christianization with the pope, the emperor and the Polish king. The conversion by force policy of the Teutonic Knights had actually been an impediment, delaying the progress of Western Christianity in the Grand Duchy.

Jogaila, a grand duke since 1377, was himself still a pagan. He agreed to become a Catholic when offered the Polish crown and the child queen Jadwiga by leading Polish nobles, who were eager to take advantage of Lithuania's expansion. Lithuania's close association with Poland had thus begun, and lasted, in one form or another, for nearly five centuries. For the near future, Poland gave Lithuania a valuable ally against increasing threats from the Teutonic Knights and the Grand Duchy of Moscow. Lithuania, in which Ruthenians outnumbered Lithuanians proper several times, was not a stable political entity, and Jogaila's realistic choice may have been between a conversion-marriage based alliance with Muscovy or with Poland. A Russian deal was also negotiated with Dmitry Donskoy in 1383–1384, but Moscow was too far to help with the Teutonic problem and could pose a difficulty as a center competing for the loyalty of the Orthodox Lithuanian Ruthenians.

Jogaila's baptism and the crowning as the King of Poland in 1386 were followed by the final and official Christianization of Lithuania.[30] The establishment of the bishopric in Vilnius in 1387 and Jogaila's orders for his court and followers to convert to Catholicism were meant to deprive the Teutonic Knights of the justification for their practice of forced conversion through military onslaughts. Jogaila also needed Polish support in his struggle with cousin Vytautas.

After the Lithuanian Civil War of 1381–1384 and the Lithuanian Civil War of 1389–1392, Vytautas the Great became the Grand Duke of Lithuania in 1392, under a compromise deal with Jogaila. Vytautas had been frustrated by Jogaila's Polish arrangements and rejected the prospect of Lithuania's subordination to Poland. During Vytautas' reign Lithuania reached the peak of its territorial expansion, but his ambitious plans were checked by the 1399 defeat, inflicted by the Golden Horde at the Battle of the Vorskla River. Prior to that expedition, in the Treaty of Salynas in 1398 Vytautas had to grant the Teutonic Order a large portion of Samogitia, a native Lithuanian land, greatly improving the position of the Order and their associated Knights of the Sword in Livonia. In his soon pursued attempts to retake the territory, the Grand Duke needed the help of the Polish King. Under Vytautas centralization of the state had begun, and the Lithuanian nobility became increasingly prominent in state politics.

The Lithuanian-Polish alliance was able to defeat the mighty Teutonic Knights at the Battle of Grunwald in 1410, but they failed to take Marienburg, the Knights' fortress-capital. Several more wars resulted and in 1422, at the Peace of Melno, the Grand Duchy recovered Samogitia, which terminated its involvement in the wars with the Order. Samogitia was the last region of Europe to be Christianized. Later different foreign policies were pursued by Lithuania and Poland, accompanied by conflicts over Podolia and Volhynia, the Grand Duchy's territories in the southeast.

The dynastic link to Poland resulted in religious, political and cultural ties and increase of Western influence among the native Lithuanian nobility, and to a lesser extent among the Ruthenian boyars from the East, Lithuanian subjects. Catholic Lithuanians were granted preferential treatment and access to offices because of the policies of Vytautas, officially pronounced in 1413 at the Union of Horodło, and even more so of his successors, aimed at asserting the rule of a Catholicized, Lithuanian elite over the Rus' territories. Such policies increased the pressure on the local nobility to convert to Catholicism. The Grand Duchy of Lithuania was preserved as a separate state with separate institutions. Cities were granted the German system of laws (Magdeburg rights), with the largest of these being Vilnius, since 1322 the capital of the Grand Duchy.

Oldest surviving manuscript in the Lithuanian language (beginning of the 16th

century), rewritten from a 15th-century original text

Under Jagiellonian rulers

Following the deaths of Vytautas (1430), conflict ensued and Lithuania was ruled by rival successors. Afterwards, the Lithuanian nobility on two occasions technically broke the union between Poland and Lithuania, unilaterally selecting grand dukes from the Jagiellon dynasty. In 1440, the Lithuanian great lords elevated Casimir, King Jagiełło's (Jogaila)'s second son. This was fixed by Casimir's election as king by the Poles in 1446. In 1492, in the case of Jagiełło's grandsons, John Albert became the king, while Alexander the grand duke in Lithuania. Again, in 1501 Alexander succeeded John as king, which resolved the difficulty.On the Teutonic front, the Polish Crown continued the struggle, which in 1466 led to the Peace of Thorn and the recovery of much of the Piast dynasty territorial losses. A secular Prussian state was established in 1525. It would greatly impact the futures of both Lithuania and Poland.

The Tatar Crimean Khanate recognized suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire from 1475. Seeking slaves and booty the Tatars raided vast portions of the Grand Duchy, burning Kiev in 1482 and approaching Vilnius in 1505. Their activity resulted in the 1480s and 1490s in Lithuania's loss of its distant reaches on the Black Sea shores. The last two Jagiellon kings were Sigismund I and Sigismund II Augustus, during whose reign the intensity of Tatar raids diminished due to the appearance of the military caste of Cossacks at the southeastern territories and the growing power of the Grand Duchy of Moscow.

The border of Lithuania's loosely controlled eastern Ruthenian territory ran in 1492 less than one hundred miles from Moscow. But as a result of the warfare, a third of the Grand Duchy's land area was ceded to the Russian state in 1503. Then the loss of Smolensk in July 1514 was particularly disastrous, even though it was followed by the successful Battle of Orsha in September, as the Polish interests were reluctantly recognizing the necessity of their own involvement in Lithuania's defense. The peace of 1537 left Homel as the Grand Duchy's eastern edge.

In the north prolonged multinational conflicts took place over the strategically and economically crucial Livonia region, the traditional territory of the Knights of the Sword. The Livonian Confederation formed an alliance with the Polish-Lithuanian side in 1557. Desired by both Lithuania and Poland, Livonia was then incorporated into the Polish Crown by Sigismund II. These developments caused Ivan IV of Russia to launch attacks in Livonia beginning in 1558, and later on Lithuania. The Grand Duchy's fortress of Polotsk fell in 1563, which was followed by a Lithuanian victory at the Battle of Ula in 1564, but not a recovery of Polotsk. Russian, Swedish and Polish-Lithuanian occupations subdivided Livonia.

The Jagiellonian dynasty founded by Jogaila (a branch of the Gediminids) ruled Poland and Lithuania continuously until 1572.

Toward more integrated union

Third Grand Duchy's Statute (1588 legal

code) was still written in the Ruthenian language. Lithuanian coat of arms, "the Chase", is shown on the title

page.

Legal evolution had lately been taking place in Lithuania nevertheless. In the Privilege of Vilnius of 1563 Sigismund restored full political rights to the Grand Duchy's Orthodox boyars, up to that time restricted by Vytautas and his successors; all members of the nobility were from then officially equal. Elective courts were established in 1565-66 and the Second Lithuanian Statute of 1566 created a hierarchy of local offices patterned on the Polish system. The Lithuanian legislative assembly assumed the same formal powers as the Polish sejm.

Lithuanian Renaissance

An influential book dealer was the humanist and bibliophile Francysk Skaryna (c. 1485—1540), who was the founding father of Belarusian letters. He wrote in his native Ruthenian (Chancery Slavonic) language and was typical in this respect of the earlier phase of the Renaissance in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, which lasted until the middle of the 16th century, when Polish predominated in literary productions. Many educated Lithuanians came back from studies abroad and the Grand Duchy was boiling with active cultural life, sometimes referred to as Lithuanian Renaissance (not to be confused with Lithuanian National Revival in the 19th century).

At the time Italian architecture was introduced in Lithuanian cities, and Lithuanian literature written in Latin flourished. Also at that time the first handwritten and printed texts in the Lithuanian language emerged, and the formation of written Lithuanian language began. The process was led by Lithuanian scholars Abraomas Kulvietis, Stanislovas Rapalionis, Martynas Mažvydas and Mikalojus Daukša.

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1569–1795)

Polish–Lithuanian

Commonwealth, History of Poland

(1569–1795), History

of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1569–1648), History

of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1648–1764), and History

of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1764–95)

Formation

With the Union of Lublin of 1569 Poland and Lithuania formed a new state: the Republic of Both Nations (commonly known as Poland-Lithuania or the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth; Polish: Rzeczpospolita Obojga Narodów, Lithuanian: Abiejų Tautų Respublika). The Commonwealth, which officially consisted of the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, was ruled by Polish and Lithuanian nobility, together with kings, who were elected by the nobles. The Union was decided to have a common foreign policy, customs and currency. Separate Polish and Lithuanian armies were kept and separate but parallel ministerial and central offices established, organized according to the governmental practice developed in the Crown. The Lithuanian Tribunal, a high court for nobility affairs, was created in 1581.Languages

The Lithuanian language fell into disuse in the circles of the grand dukes' courts in the second half of the 15th century. A century later Polish was commonly used by ordinary Lithuanian nobility. Following the Union of Lublin, Polonization increasingly affected all aspects of Lithuanian public life, but it took well over a century for the process to be completed. The 1588 Third Statute of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the earlier legal codifications were written in the Ruthenian Chancery Slavonic language. From about 1700 Polish was used in the Grand Duchy's official documents, replacing the previous Ruthenian and Latin use.Lithuania's ruling families and nobility had become linguistically and culturally Polonized, while retaining a sense of Lithuanian identity. The integrating process of the Commonwealth nobility was not regarded as Polonization in the sense of modern nationality, but rather as participation in the Sarmatism cultural-ideological current, erroneously understood to imply also a common (Sarmatian) ancestry of all members of the noble class The Lithuanian language however survived, despite the encroachments of the Ruthenian, Polish, Russian, Belarusian and German languages, as a peasant vernacular and from 1547 in written religious use.Western Lithuania had an important role in the preservation of the Lithuanian language and its culture. In Samogitia many nobles never ceased to speak Lithuanian natively. Lithuania Minor region in Prussia was populated mainly by Lithuanians and religiously dominated by Lutheran Reformation. The Lutherans promoted publishing of religious books in local languages, which is why Catechism by Martynas Mažvydas was printed in Lithuanian in 1547 in nearby Königsberg.

Religion

Hetman

Kristupas Radvila or Krzysztof Radziwiłł (1585–1640),

a Lithuanian Calvinist and an

accomplished military commander

By 1750 nominal Catholics comprised about 80% of the Commonwealth's population, the vast majority of the noble citizenry, and the entire legislature. In the east there were also the Eastern Orthodox Church adherents. However, Catholics in the Grand Duchy itself were split. Under half were Latin rite with strong allegiance to Rome. The others (mostly non-noble Ruthenians) followed the Eastern rite. They were the so-called Uniates, whose church was established at the Union of Brest in 1596, and they acknowledged only nominal obedience to Rome. At first the advantage went to the advancing Roman Catholic Church pushing back a retreating Orthodox Church. However after the first partition of the Commonwealth in 1772, the Orthodox had the support of the government and gained the upper hand. The Russian Orthodox Church paid special attention to the Uniates (who had once been Orthodox), and tried to bring them back. The contest was political and spiritual, using missionaries, schools, and pressure exerted by powerful nobles and landlords. By 1800 over 2 million of the Uniates had become Orthodox, and another 1.6 million by 1839.[59][60]

Grand Duchy, its grandeur and decline[edit]

The Union of Lublin and the integration of the two countries notwithstanding, for over two centuries Lithuania continued to exist as the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, retaining separate laws as well as an army and a treasury. At the time of the Union King Sigismund II Augustus removed Ukrainian and other territories from Lithuania and incorporated them into the Polish Crown. The Grand Duchy was left with today's Belarus and parts of western Russia, in addition to its ethnic Lithuanian lands. From 1573, the kings of Poland and the grand dukes of Lithuania were always the same person and were elected by the nobility, who were granted ever increasing liberties and privileges. These liberties, especially the liberum veto, led to political anarchy and the eventual dissolution of the state.Within the Commonwealth, the Grand Duchy made important contributions to the Western and Eastern civilizations of Europe: Western Europe was supplied with grain, along the Danzig to Amsterdam sea route; the early Commonwealth's religious tolerance and democracy among the ruling noble class were unique in Europe; Vilnius was the only European capital located on the border of the worlds of the Western and Eastern Christianity and many religious faiths were practiced there; to the Jews, it was the "Jerusalem of the North" and the town of the Vilna Gaon, their great religious leader; the Vilnius University produced numerous illustrious alumni and was one of the most influential centers of learning in its part of Europe; the Vilnius school of Baroque made significant contributions to European architecture; the Lithuanian legal tradition gave rise to the Lithuanian Statutes, advanced legal codes; at the end of the Commonwealth's existence the first comprehensive written constitution in Europe was produced. After the Partitions, the Vilnius school of Romanticism produced the two great poets: Adam Mickiewicz and Juliusz Słowacki.

The Commonwealth was greatly weakened by a series of wars, beginning in 1648 with Khmelnytsky's Cossack uprising. During the Northern Wars (1655–1661), the Lithuanian territory and economy were devastated by the Swedish army and Vilnius was burned and looted by the Russian forces. Before it could fully recover, Lithuania was again ravaged during the Great Northern War (1700–1721).

War, plague, and famine resulted in the loss of approximately 40% of the country's inhabitants. Foreign powers, especially Russia, became dominant players in the domestic politics of the Commonwealth. Numerous factions among the nobility, controlled and manipulated by the powerful magnate families, themselves often in conflict, used their "Golden Liberty" to prevent reforms. Some Lithuanian clans, such as the Radziwiłłs, counted among the most powerful of Commonwealth nobles.

The Constitution of May 3, 1791, a culmination of the belated reform process of the Commonwealth, was passed by the Sejm (central legislature). It attempted to integrate Lithuania and Poland more closely, although the separation was kept by the added Reciprocal Guarantee of Two Nations. Partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1772, 1793 and 1795 terminated the existence of the Commonwealth and saw the Grand Duchy of Lithuania divided between the Russian Empire, which took over 90% of the Duchy's territory, and the Kingdom of Prussia. The Third Partition took place after the failure of the Kościuszko Uprising, the last war waged by Poles and Lithuanians to preserve their statehood. Lithuania ceased to exist as a distinct entity for more than a century.

Under Imperial Russia, World War I (1795–1918)

Post-Commonwealth Lithuania (1795–1864); foundations of Lithuanian nationalism

These hopes were soon to be dashed, particularly subsequent to 1812, when Lithuanians eagerly welcomed Napoleon Bonaparte's French army as liberators, with many joining his offensive against Russia. After the French army's defeat and withdrawal, Tsar Alexander I decided to keep the University of Vilnius open and the poet Adam Mickiewicz was able to receive his education there. The south-western part of Lithuania included in Prussia in 1795 and in the short-lived Duchy of Warsaw established in 1807 became a part of the Russian-controlled Kingdom of Poland in 1815, while the rest of Lithuania continued to be administered as a Russian province.

Lithuanians and Poles revolted twice, in 1831 and 1863, but both attempts had failed and resulted in increased repression by the Russian authorities. After the November Uprising of 1831, Tsar Nicholas I began an intensive program of Russification and the University of Vilnius was closed. Lithuania became part of a new administrative region called Northwestern Krai (the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania). The Polish language schooling and cultural life were however largely able to continue in the former Grand Duchy, until the failure of the 1863 January Uprising. The Statutes of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania were annulled by the Russian Empire only in 1840, and serfdom was abolished in 1861. The Uniate Church, important in the Belarus part of the former Grand Duchy, was incorporated into the Orthodox Church in 1839]

The poetry of Adam Mickiewicz, emotionally attached to the Lithuanian setting and exploring Lithuania's medieval themes, influenced ideological foundations of the emerging Lithuanian national movement. Simonas Daukantas, who studied with Mickiewicz at Vilnius, promoted a return to Lithuania's pre-Commonwealth traditions and a renewal of the local culture, based on the Lithuanian language. With those ideas in mind he wrote already in 1822 (at that time not published) a history of Lithuania in Lithuanian. Teodor Narbutt wrote in Polish a voluminous Ancient History of the Lithuanian Nation (1835–1841), where he likewise expounded and expanded further the concept of historic Lithuania, whose days of glory had ended with the union with Poland (1569). Narbutt, invoking the German scholarship, pointed out the relationship between the Lithuanian and Sanskrit languages. It indicated the closeness of Lithuanian (preserved in considerable isolation from historic era foreign influences) to its old Indo-European roots and would later provide the "antiquity" argument for the national revival activists. By the middle of the 19th century the basic ideology of the future nationalist movement had thus been defined; it required, in order to establish a modern Lithuanian identity, a break with the Polish (early modern) tradition and cultural-linguistic dependence.

Around the time of the January Uprising, there was a generation of Lithuanian leaders of the transitional period, between the Grand Duchy-oriented, bound with Poland, and the modern nationalist Lithuanian language-based movement. Jakób Gieysztor, Konstanty Kalinowski and Antanas Mackevičius wanted to form alliances with the local (Lithuanian and Belarusian speaking) peasants, who, empowered and given land, would presumably help defeat the Russian Empire, acting in their own self-interest. This created new dilemmas that had to do with languages used for such inter-class communication, and later led to the concept of a nation as the "sum of speakers of a vernacular tongue".

Formation of modern national identity and push for self-rule (1864–1918)

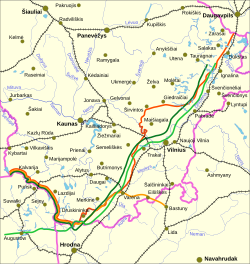

Modern Lithuania with the former Russian Empire's

administrative divisions (governorates) shown (1867–1914)

The Russian Empire regarded the Grand Duchy of Lithuania as an East Slavic realm that ought to be (and was being) "reunited" with Russia. In the following decades however, a national, Lithuanian ethnicity-based movement emerged. It was composed of activists of different social backgrounds and persuasions, often primarily Polish speaking, but united by their willingness and zeal to promote the Lithuanian culture and language as a strategy for building a modern nation. The restoration of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania was no longer the objective of this movement and the territorial ambitions of its leaders were limited to the lands they considered (in the historic sense) ethnically Lithuanian.

Because many Lithuanian nobles were Polonized and only the poor and middle classes used Lithuanian (some of the latter also preferred to use Polish), Lithuanian was not considered a prestigious language. There were even expectations that the language would become extinct, as more and more territories in the east were Slavicized, and more people used Polish or Russian in daily life. The only place where Lithuanian was considered more prestigious and worthy of books and studying was the German-controlled Lithuania Minor. Even there, an influx of German immigrants threatened the native language and culture.

The language was already present among poor people and the language revival spread into more affluent strata, beginning with the release of Lithuanian newspapers, Aušra and Varpas, then with the writing of poems and books in Lithuanian. These writings glorified the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, depicting the historic nation of great power and with many heroes.

Basanavičius studied medicine at Moscow, where he developed international connections, published in Polish on Lithuanian history and graduated in 1879. From there he went to Bulgaria, and in 1882 moved to Prague. In Prague he met and became influenced by the Czech national movement activists. In 1883 Basanavičius began working on a Lithuanian language review, which assumed the form of a newspaper named Aušra (The Dawn). Published in German East Prussia, Aušra was written in the Latin script, banned under the Russian rule where Cyrillic characters were required for printing in Lithuanian, and was smuggled to Lithuania, together with other Lithuanian publications and books. The review (forty issues in total), building on the work of the earlier writers, sought to establish continuities with the medieval Grand Duchy of Lithuania and exalted the Lithuanian common people in their role as the conduit of that (essential for the national revival) continuity.

The revival spearheaded the independence movement, with various organizations opposing Russian influence. Russian policy became harsher in response. Attacks took place against Catholic churches while a ban forbidding Lithuanian press continued.

The period from 1890 to 1904 (when the Russian ban was lifted) saw the publication of about 2,500 book titles in the Lithuanian Latin alphabet. The majority of these were published in Tilsit, a city in East Prussia, although some publications reached Lithuania from the United States. A largely standardized written version of the language was achieved by the turn of the twentieth century, based on historical and Aukštaitijan (highland) usages. The letters -č-, -š- and -v- were taken from the modern (redesigned) Czech orthography, to avoid the Polish usage for corresponding sounds. The widely accepted Lithuanian Grammar, by Jonas Jablonskis, appeared in 1901.

In 1879 Emperor Alexander II of Russia approved a proposal from the Russian military leadership to build the largest defensive structure in the entire Russian state – the 65 km2 (25 sq mi) Kaunas Fortress. Large numbers of Lithuanians went to the United States in 1867–1868 after a famine in Lithuania] Between 1868 and 1914, approximately 635,000 people, almost 20% of the population, left Lithuania. Lithuanian cities and towns were growing under the Russian rule, but the country remained underdeveloped by the European standards and job opportunities were limited; many Lithuanians left also for the industrial centers of the Empire, such as Riga and Saint Petersburg. Many cities in Lithuania were dominated by Jews and Polish-speaking people. Nevertheless, a Lithuanian National Revival movement laid the foundations of the modern Lithuanian nation and independent Lithuania.

A flyer with a proposed agenda for the Great

Seimas of Vilnius; it was rejected by the delegates and a more politically

activist schedule was adopted

After the outbreak of hostilities in World War I Germany occupied Lithuania and Courland in 1915. Vilnius fell to the Germans on 19 September 1915. An alliance with Germany in opposition to both tsarist Russia and Lithuanian nationalism became for the Baltic Germans a real possibility. Lithuania was incorporated into Ober Ost, occupational German government. As open annexation could result in a public relations backlash, the Germans planned to form a network of formally independent states that would in fact be completely dependent on Germany, the so-called Mitteleuropa.

Independent Lithuania (1918–40)

Declaration of independence

Germany lost the war and signed the Armistice of Compiègne on 11 November 1918. Lithuanians quickly formed their first government, led by Augustinas Voldemaras, adopted a provisional constitution, and started organizing basic administrative structures. As the German army, defeated in the West, was withdrawing from the Eastern Front, it was followed by the Soviet forces, whose intention was to spread the global proletarian revolution. They created a number of puppet states, including on 16 December 1918 the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic. By the end of December the Red Army reached Lithuanian borders, starting the Lithuanian–Soviet War.

From April 1919, the Lithuanian–Soviet War went parallel with the Polish–Soviet War. Polish troops captured Vilnius from the Soviets on 21 April 1919. Poland had territorial claims over Lithuania, especially the Vilnius Region, and these tensions spilled over into the Polish–Lithuanian War. Józef Piłsudski of Poland, seeking a Polish-Lithuanian federation, but unable to find common ground with Lithuanian politicians, in August 1919 made an unsuccessful attempt to overthrow the Lithuanian government in Kaunas.

In mid-May the Lithuanian army, commanded by General Silvestras Žukauskas, began an offensive against the Soviets in northeastern Lithuania. By the end of August 1919, the Soviets were pushed out of the Lithuanian territory. The Lithuanian army was then deployed against the paramilitary West Russian Volunteer Army, who invaded northern Lithuania. They were Germany-reactivated and supported German and Russian soldiers who sought to retain German control over the former Ober Ost. West Russian Volunteers were defeated and pushed out by the end of 1919. Thus the first phase of the Lithuanian Wars of Independence was over and Lithuanians could direct attention to internal affairs.

Democratic Lithuania

The Constituent Assembly of Lithuania was elected in April and first met in May 1920. In June it adopted the third provisional constitution and on 12 July 1920 signed the Soviet–Lithuanian Peace Treaty. In the treaty the Soviet Union recognized fully independent Lithuania and its claims to the disputed Vilnius Region; Lithuania secretly allowed the Soviet forces passage through its territory, as they moved against Poland. On 14 July 1920, the advancing Soviet army captured Vilnius for a second time from Polish forces. However, they only handed the city over to Lithuanians on 26 August 1920, following the defeat of the Soviet offensive. The victorious Polish army returned and the Soviet–Lithuanian Treaty increased hostilities between Poland and Lithuania. To prevent further fighting, the Suwałki Agreement was signed on 7 October 1920; it left Vilnius on the Lithuanian side of the armistice line. It had never gone into effect, because Polish General Lucjan Żeligowski, acting on Józef Piłsudski's orders, staged a military action presented as a mutiny. He invaded Lithuania on 8 October 1920, captured Vilnius the following day, and established in eastern Lithuania a short-lived Republic of Middle Lithuania on 12 October 1920. The "Republic" was a part of Piłsudski's federalist scheme, which was never to materialize, because of the opposition from both the Polish and Lithuanian (represented now by the Lithuanian government) nationalists.

Lithuanian-Polish territorial disputes in the early

1920s: the "Republic of Middle Lithuania"

(green)

The Constituent Assembly, which adjourned in October 1920 due to threats from Poland, gathered again and initiated many reforms needed in the new state: obtained international recognition and membership in the League of Nations, passed the law of land reform, introduced national currency litas, and adopted the final constitution in August 1922. Lithuania became a democratic state, with Seimas (parliament) elected by men and women for a three-year term. The Seimas elected the president. The First Seimas was elected in October 1922, but could not form a government as the votes split equally 38–38, and was forced to resign. Its only lasting achievement was the Klaipėda Revolt from 10–15 January 1923.

The Second Seimas, elected in May 1923, was the only Seimas in independent Lithuania that served the full term. The Seimas continued the land reform, introduced social support systems, started repaying foreign debt. A national census took place in 1923.

Authoritarian Lithuania

Antanas Smetona, the first and last president

of independent Lithuania during the interbellum. The 1918–1939 period if often known as

"Smetona's time".

The Seimas thought that the coup was just a temporary measure and new elections should be called to return Lithuania to democracy. The legislative body was dissolved in May 1927. Later that year members of the Social Democrats and other leftist parties, named plečkaitininkai after their leader, tried to organize an uprising against Smetona but were quickly subdued. Voldemaras grew increasingly independent of Smetona and was forced to resign in 1929. Three times in 1930 and once in 1934 he unsuccessfully attempted to return to power. In May 1928 Smetona, without the Seimas, announced the fifth provisional constitution. It continued to claim that Lithuania is a democratic state and vastly increased powers of the President. His party, the Lithuanian Nationalist Union, steadily grew in size and importance. Smetona adopted the title of "tautos vadas" (leader of the nation) and slowly started building personality cult. Many of the prominent political figures married into Smetona's family (Juozas Tūbelis, Stasys Raštikis).

When the Nazi Party came into power in the Weimar Republic, Germany–Lithuania relations worsened considerably as Nazi Germany did not accept the loss of the Klaipėda Region. The Nazis sponsored anti-Lithuanian organizations in the region. In 1934, Lithuania put the activists on trial and sentenced about 100 people, including their leaders Ernst Neumann and Theodor von Sass. That prompted Germany, one of the main trade partners of Lithuania, to declare embargo of Lithuanian products. In response Lithuania shifted its exports to Great Britain. But that was not enough and peasants in Suvalkija organized strikes, which were violently suppressed. Smetona's prestige was damaged and in September 1936 he agreed to call the first elections to Seimas since the coup of 1926. Before the elections all political parties, except the National Union, were eliminated. Thus of the 49 members of the Fourth Seimas, 42 were from the National Union. It functioned as an advisory board to the President and in February 1938 adopted a new constitution, which granted the President even greater powers.

As tensions were rising in Europe following the annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany, Poland presented an ultimatum to Lithuania in March 1938. Poland demanded the re-establishment of normal diplomatic relations, which were broken after the Żeligowski's Mutiny in 1920, and threatened military actions in case of refusal. Lithuania, having a weaker military and unable to enlist international support for its cause, accepted the ultimatum. Lithuania–Poland relations somewhat normalized and the parties concluded treaties regarding railway transport, postal exchange, and other means of communication.

With many countries, including France and Estonia, supporting Poland in the conflict over Vilnius, Lithuania pursued policies friendly to Germany and the Soviet Union, but both powers soon encroached on Lithuania's territory and independence. Just a year after the Polish ultimatum and five days after the German occupation of Czechoslovakia, Lithuania received an oral ultimatum from Joachim von Ribbentrop demanding to cede the Klaipėda Region to Germany. Again, Lithuania was forced to accept. This triggered a political crisis in Lithuania and forced Smetona to form a new government which for the first time since 1926 included members of the opposition. The loss of Klaipėda was a major blow to Lithuanian economy and the country shifted to the sphere of German influence. When Germany and the Soviet Union concluded the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact in 1939 and divided Eastern Europe into spheres of influence, Lithuania was, at first, assigned to Germany, but that was changed after Smetona's refusal to participate in the German invasion of Poland.

The interwar period of independence gave birth to the development of Lithuanian press, literature, music, arts, and theater as well as a comprehensive system of education with Lithuanian as the language of instruction. The network of primary and secondary schools was expanded and institutions of higher learning were established in Kaunas. Lithuanian society remained heavily agricultural with only 20% of the people living in cities. The influence of the Catholic Church was strong and birth rates high: the population increased by 22% to over three million during 1923-1939, despite emigration to South America and elsewhere.

World War II (1939–45)

Joseph Stalin, Joachim von Ribbentrop and others at the

signing of the German–Soviet

Boundary and Friendship Treaty

In 1940, once the Winter War in Finland was over and Germany was making rapid advances against Denmark and Norway and against France and the Low Countries, the Soviets heightened their diplomatic pressure on Lithuania, culminating in the Soviet ultimatum to Lithuania of June 14, 1940. The ultimatum demanded the formation of a new pro-Soviet government and admission of an unspecified number of Russian troops. Lithuania, already partially controlled by Soviet forces and unable to effectively resist, accepted the ultimatum. President Antanas Smetona fled Lithuania as the Soviet military (15 divisions with 150,000 soldiers) crossed the Lithuanian border on June 15, 1940.

Immediately following the occupation, Soviet authorities began rapid Sovietization of Lithuania. All land was nationalized. To gain support for the new regime among the poorer peasants, large farms were distributed to small landowners. However, in preparation for eventual collectivization, agricultural taxes were dramatically increased in an attempt to bankrupt all farmers. Nationalization of banks, larger enterprises, and real estate resulted in disruptions in production causing massive shortages of goods. The Lithuanian litas was artificially undervalued and withdrawn by spring 1941. The standard of living plummeted. All religious, cultural, and political organizations were banned leaving only the Communist Party of Lithuania and its youth branch. An estimated 12,000 "enemies of the people" were arrested. During the June 1941 deportation campaign, some 12,600 people (mostly former military officers, policemen, political figures, intelligentsia and their families) were deported, under the policy of elimination of national elites, to Gulags in Siberia, where many perished due to inhumane conditions; 3,600 were imprisoned and over 1,000 killed.

Nazi occupation

Collaboration and resistance

Lithuanians also organized armed resistance, which was conducted by pro-Soviet partisans, operated in eastern Lithuania, and mainly consisted of minority Russians, Belarusians and Jews. This group fought for the re-incorporation of Lithuania into the Soviet Union. Soviet partisans committed a number of atrocities (for example, the Koniuchy massacre) and sacked towns and villages. The villagers were forced to organize local self-defense. The Polish Armia Krajowa (AK) also operated in eastern Lithuania, expecting post-war Poland to resume control of the Vilnius Region. AK was fighting not only against the Nazis, but also against the pro-Nazi Lithuanian police involved in attacks on Poles, Lithuanian Territorial Defense Force, and the Soviet partisans. Relationships between different national military organizations were often adversarial and became only more hostile and retributive as the war went on.

The Holocaust

Return of Soviet authority

In the summer of 1944, the Soviet Red Army reached eastern Lithuania. By July 1944, the area around Vilnius came under control of the Polish Resistance fighters of Armia Krajowa, who also attempted a takeover of the German-held city during the ill-fated Operation Ostra Brama. The Red Army captured Vilnius with Polish help on 13 July. The USSR re-occupied Lithuania and Joseph Stalin re-established the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic in 1944 with its capital in Vilnius. The Soviets secured the passive agreement of the United States and Britain (see Yalta Conference and Potsdam Agreement). By January 1945, the Soviets captured Klaipėda, on the Baltic coast. It is estimated that Lithuania lost 780,000 people between 1940 and 1954, under the Nazi and then Soviet occupations.Soviet Lithuania (1944–90)

Stalinism and Soviet rule (1944–88)

Antanas Sniečkus was the leader of the Communist Party of Lithuania for

34 years. He was instrumental to the Lithuanization of Vilnius and helped prevent the

city from being Russified.

See also: Forest Brothers

Soviet authorities encouraged immigration of non-Lithuanian workers,

especially Russians, as a way of integrating Lithuania into the Soviet Union and

to encourage industrial development, but in Lithuania this process had not assumed the massive scale experienced by

other European Soviet republics.Between Stalin's death and the reforms of Mikhail Gorbachev Lithuania functioned as a Soviet society, with all its repressions and peculiarities. Agriculture remained collectivized, property nationalized, criticism of the Soviet system was severely punished. The country remained largely isolated from the non-Soviet world because of travel restrictions, the persecution of the Catholic Church continued and the nominally egalitarian society was extensively corrupted by the practice of connections and privileges for those who served the system.

The communist era is memorialized in Grūtas Park.

Rebirth (1988–90)

Independent modern Lithuania (1990–present)

Struggle for independence (1990–91)

On March 15, the Soviet Union demanded revocation of the independence and began employing political and economic sanctions against Lithuania. Soviet military was used to seize a few public buildings, but violence was largely contained until January 1991. During the January Events, the Soviet authorities attempted to overthrow the elected government by sponsoring the so-called National Salvation Committee. The Soviets forcibly took over the Vilnius TV Tower, killing 14 unarmed civilians and injuring 700.During this assault the only means of contact to the outside world available was an amateur radio station set up in the Lithuanian Parliament building by Tadas Vyšniauskas whose call sign was LY2BAW. Their initial cries for help were received by an American amateur radio operator with the call sign N9RD in Indiana, USA. N9RD and later other radio operators from around the world were able to relay situational updates to relevant authorities until official State Department personnel were able to go on-air. Moscow failed to act further to crush the Lithuanian independence movement and the Lithuanian government continued to work.

During the national referendum on February 9, 1991, more than 90% of those who took part in the voting (76% of all eligible voters) voted in favor of an independent, democratic Lithuania. During the August Coup in Moscow, Soviet military troops took over several communications and other government facilities in Vilnius and other cities, but returned to their barracks when the coup failed. The Lithuanian government banned the Communist Party and ordered confiscation of its property. Following the failed coup, Lithuania received widespread international recognition and was admitted to the United Nations on September 17, 1991.

Contemporary Republic of Lithuania (1991–present)

As in many other formerly Soviet countries, popularity of the independence movement (Sąjūdis in the case of Lithuania) was diminishing due to worsening economic situation (rising unemployment, inflation, etc.). The Lithuanian Communist Party renamed itself Democratic Labour Party of Lithuania (LDDP) and ran against Sąjūdis in the 1992 parliamentary elections, gaining a majority of the seats. LDDP continued building the independent democratic state and transitioning from a centrally planned to a free market economy. In the 1996 parliamentary elections, the voters swung back to the rightist Homeland Union, led by the former Sąjūdis leader Vytautas Landsbergis.As part of the economic transition, Lithuania organized a privatization campaign to sell government-owned residential real estate and commercial enterprises. The government issued investment vouchers to be used in privatization instead of actual currency. People cooperated in groups to collect larger amounts of vouchers for the public auctions and the privatization campaign. Lithuania, unlike Russia, did not create a small group of very wealthy and powerful people. The privatization started with small organizations, and large enterprises (such as telecoms or airlines) were sold several years later for hard currency in a bid to attract foreign investors. Lithuania's monetary system was to be based on litas, the currency used during the interwar period. Due to high inflation and other delays a temporary currency, talonas, was introduced (commonly called Vagnorkė or Vagnorėlis after Prime Minister Gediminas Vagnorius). Eventually litas was issued in June 1993 and it was decided to peg it to the United States dollar in 1994 and to the Euro in 2002.

On April 27, 1993, a partnership with the Pennsylvania National Guard was established as part of the State Partnership Program.

Seeking closer ties with the West, Lithuania applied for the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) membership in 1994. The country had to go through a difficult transition from planned to free market economy, satisfying the requirements for the European Union (EU) membership. In May 2001, Lithuania became the 141st member of the World Trade Organization. In October 2002, Lithuania was invited to join the European Union and one month later to join the North Atlantic Treaty Organization; it became a member of both in 2004.

As a result of the broader global financial crisis, the Lithuanian economy in 2009 experienced its worst recession since gaining independence from the Soviet Union in 1991. After a boom in growth sparked by Lithuania’s 2004 accession to the European Union, the GDP contracted by 15% in 2009. Especially since the EU joining, large numbers of Lithuanians (up to 20% of the population) moved abroad in search of better economic opportunities, creating a significant demographic problem for the small country.