Wednesday, July 31, 2013

90. Algeria- Introduction

Algeria , officially The People's Democratic Republic of Algeria, is a country in North Africa on the Mediterranean coast. Its capital and most populous city is Algiers. Algeria is a semi-presidential republic, it consists of 48 provinces and 1541 communes. With a population exceeding 37 million, it is the 34th most populated country on Earth. With an economy based on oil resources, manufacturing has suffered from what is called Dutch disease. Sonatrach, the national oil company, is the largest company in Africa. Algeria has the second largest army with the largest defense budget in Africa. Algeria had a peaceful Nuclear Program by the 1990s.

With a total area of 2,381,741 square kilometres (919,595 sq mi), Algeria is the tenth-largest country in the world, and the largest in Africa and in the Mediterranean. The country is bordered in the northeast by Tunisia, in the east by Libya, in the west by Morocco, in the southwest by Western Sahara, Mauritania, and Mali, in the southeast by Niger, and in the north by the Mediterranean Sea. Algeria is a member of the African Union, the Arab League, OPEC and the United Nations, and is a founding member of the Arab Maghreb Union.

Geographically, Morocco, Tunisia, and Algeria form one great natural area, with the same physical characyeristics and a climate common to all three countries, of which Algeria forms the centrepiecs. The Algerian coast line, 850 miles long, is highly fertile which is known as "Tell"Until the 1920s the main product was cotton and tobacco with olive oil as th third one.

The territory of today's Algeria was the home of many ancient prehistoric cultures, including Aterian and Capsian cultures. Its area has known many empires and dynasties, including ancient Berber Numidians, Carthaginians, Romans, Vandals, Byzantines, Arab Umayyads, Berber Fatimids, Berber Almoravids, Berber Almohads and later Turkish Ottomans.

The country's name derives from the city of Algiers. The most common etymology links the city name to

( "The Islands"), a truncated form of the city's older name Jazā'ir Banī Mazghanna employed by medieval geographers such as al-Idrisi. Others trace it to Ldzayer, the Maghrebi Arabic and Berber for "Algeria" possibly related to the Zirid Dynasty King Ziri ibn-Manad and founder of the city of Algiers.

Rank and economy of Namibia

The rank of Namibia from the poorest of the countries is 89th and from the richest is 115 with national average per capita income using atlas method in 2003.

In other methods such as IMF, WB, and CIA using nominal methods in 2007, 2007, and 2008,

IMF/Measure..................WB/Measure.................CIA/measure

93/3,671........................89/3,250...........................96/3,577

In other methods such as IMF, WB, and CIA using nominal methods in 2007, 2007, and 2008,

IMF/Measure..................WB/Measure.................CIA/measure

93/3,671........................89/3,250...........................96/3,577

| Rank | 131st |

|---|---|

| Currency |

Namibian dollar

(NAD) (South African Rand) |

| Fiscal year | 1 April - 31 March |

| Trade organisations | WTO, SADC, SACU |

| Statistics | |

| GDP | $13.764 billion (2009 IMF) |

| GDP growth | -0.739% (2009 IMF) |

| GDP per capita | $6,610 (2009 IMF.) |

| GDP by sector | agriculture: 9.5%, mining: 12.4%, manufacturing: 15.4% (2007) |

| Inflation (CPI) | 7.1% (2011) |

| Population below poverty line |

34.9% of the population live on $1 per day and 55.8% live on $2 per day |

| Labour force | 820,000 (2005 est.) |

| Labour force by occupation |

agriculture: 47%, industry: 20%, services: 33% (1999 est.) |

| Unemployment | 52% (Broad Definition) (2008) |

| Main industries | meatpacking, fish processing, dairy products; mining (diamonds, lead, zinc, tin, silver, tungsten, uranium, copper) |

| Ease of Doing Business Rank | 78th |

| External | |

| Exports | $2.04 billion f.o.b. (2005 est.) |

| Export goods | diamonds, copper, gold, zinc, lead, uranium; cattle, processed fish, karakul skins |

| Main export partners | South Africa 33.4%, US 4% (2004) |

| Imports | $2.35 billion f.o.b. (2005 est.) |

| Import goods | foodstuffs; petroleum products and fuel, machinery and equipment, chemicals |

| Main import partners | South Africa 85.2%, US (2004) |

| Public finances | |

| Public debt | NAD 17.2 billion (March 2012) |

| Revenues | $1.945 billion (2005) |

| Expenses | $2.039 billion (2005) |

| Economic aid | recipient: ODA, $160 million (2000).[edit]Namibia is a higher middle income country with an estimated annual GDP per capita of US$5,828 but has extreme inequalities in income distribution and standard of living.[6] It leads the list of countries by income inequality with a Gini coefficient of 70.7 (CIA)[7] and 74.3 (UN),[8] respectively.Since independence, the Namibian Government has pursued free-market economic principles designed to promote commercial development and job creation to bring disadvantaged Namibians into the economic mainstream. To facilitate this goal, the government has actively courted donor assistance and foreign investment. The liberal Foreign Investment Act of 1990 provides guarantees against nationalisation, freedom to remit capital and profits, currency convertibility, and a process for settling disputes equitably. Namibia also is addressing the sensitive issue of agrarian land reform in a pragmatic manner. However, Government runs and owns a number of companies such as Air Namibia, Transnamib and NamPost, most of which need frequent financial assistance to stay afloat.[9][10] The country's sophisticated formal economy is based on capital-intensive industry and farming. However, Namibia's economy is heavily dependent on the earnings generated from primary commodity exports in a few vital sectors, including minerals, especially diamonds, livestock, and fish. Furthermore, the Namibian economy remains integrated with the economy of South Africa, as the bulk of Namibia's imports originate there. In 1993, Namibia became a signatory of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) signatory, and the Minister of Trade and Industry represented Namibia at the Marrakech signing of the Uruguay Round Agreement in April 1994 . Namibia also is a member of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, and has acceded to the European Union's Lomé Convention. |

Industry in Namibia

Sectors

Namibia is heavily dependent on the extraction and processing of minerals for

export. Taxes and royalties from mining

account for 25% of its revenue. The bulk of the

revenue is created by diamond mining, which made up 7.2% of the 9.5% that mining

contributes to Namibia's GDP in 2011. Rich alluvial diamond deposits make Namibia a primary source for gem-quality

diamonds.Mining and energy

Diamond production totalled 1.5 million carats (300 kg) in 2000, generating nearly $500 million in export earnings. Other important mineral resources are uranium, copper, lead, and zinc. The country also is a source of gold, silver, tin, vanadium, semiprecious gemstones, tantalite, phosphate, sulfur, and salt.Namibia is the fourth-largest exporter of nonfuel minerals in Africa, the world's fifth-largest producer of uranium, and the producer of large quantities of lead, zinc, tin, silver, and tungsten. The mining sector employs only about 3% of the population while about half of the population depends on subsistence agriculture for its livelihood. Namibia normally imports about 50% of its cereal requirements; in drought years food shortages are a major problem in rural areas.

During the pre-independence period, large areas of Namibia, including off-shore, were leased for oil prospecting. Some natural gas was discovered in 1974 in the Kudu Field off the mouth of the Orange River, but the extent of this find is only now being determined.

Fishing

The clean, cold South Atlantic waters off the coast of Namibia are home to some of the richest fishing grounds in the world, with the potential for sustainable yields of 1.5 million metric tonnes per year. Commercial fishing and fish processing is the fastest-growing sector of the Namibian economy in terms of employment, export earnings, and contribution to GDP.The main species found in abundance off Namibia are pilchards (sardines), anchovy, hake, and horse mackerel. There also are smaller but significant quantities of sole, squid, deep-sea crab, rock lobster, and tuna.

At the time of independence, fish stocks had fallen to dangerously low levels, due to the lack of protection and conservation of the fisheries and the over-exploitation of these resources. This trend appears to have been halted and reversed since independence, as the Namibian Government is now pursuing a conservative resource management policy along with an aggressive fisheries enforcement campaign. The government seeks to develop fish-farming as an alternative.

Manufacturing and infrastructure

In 2000, Namibia's manufacturing sector contributed about 20% of GDP. Namibian manufacturing is inhibited by a small domestic market, dependence on imported goods, limited supply of local capital, widely dispersed population, small skilled labour force and high relative wage rates, and subsidised competition from South Africa.Walvis Bay is a well-developed, deepwater port, and Namibia's fishing infrastructure is most heavily concentrated there. The Namibian Government expects Walvis Bay to become an important commercial gateway to the Southern African region.

Namibia also boasts world-class civil aviation facilities and an extensive, well-maintained land transportation network. Construction is underway on two new arteries—the Trans-Caprivi Highway and Trans-Kalahari Highway—which will open up the region's access to Walvis Bay.

The Walvis Bay Export Processing Zone operates in the key port of Walvis Bay.

Labour

While many Namibians are economically active in one form or another, the bulk of this activity is in the informal sector, primarily subsistence agriculture. A large number of Namibians seeking jobs in the formal sector are held back due to a lack of necessary skills or training. The government is aggressively pursuing education reform to overcome this problem.

Namibia has a high unemployment rate. "Strict unemployment" (people actively seeking a full-time job) stood at 20.2% in 1999, 21.9% in 2002 and spiraled to 29,4 per cent in 2008. Under a broader definition (including people that have given up searching for employment) unemployment rose from 36.7% in 2004 to 51.2% in 2008. This estimate considers people in the informal economy as employed. 72% of jobless people have been unemployed for two years or more. Labour and Social Welfare Minister Immanuel Ngatjizeko praised the 2008 study as "by far superior in scope and quality to any that has been available previously", but its methodology has also received criticism.The total number of formally employed people is decreasing steadily, from about 400,000 in 1997 to 330,000 in 2008, according to a government survey. Of annually 25,000 school leavers only 8,000 gain formal employment—largely a result of a failed education system

Namibia's largest trade union federation, the National Union of Namibian Workers (NUNW) represents workers organised into seven affiliated trade unions. NUNW maintains a close affiliation with the ruling SWAPO party.

Agriculture in Namibia

As of 2010, the Minister of Agriculture, Water, and Forestry is John Mutorwa. The Ministry operates a number of parastatals, including NamWater.

Although Namibian agriculture--excluding fishing--contributed between 5% and 6% of Namibia's GDP from 2004-2009, a large percentage of the Namibian population depends on agricultural activities for livelihood, mostly in the subsistence sector. Animal products, live animals, and crop exports constituted roughly 10.7% of total Namibian exports. The government encourages local sourcing of agriculture products. Retailers of fruits, vegetables, and other crop products must purchase 27.5% of their stock from local farmers.

The government's land reform policy is shaped by two key pieces of legislation: the Agricultural (Commercial) Land Reform Act 6 of 1995 and the Communal Land Reform Act 5 of 2002. The government remains committed to a "willing seller, willing buyer" approach to land reform and to providing just compensation as directed by the Namibian constitution. As the government addresses the vital land and range management questions, water use issues and availability are considered.

Tuesday, July 30, 2013

Rivers of Namibia

Flowing into the Atlantic Ocean

Kunene River

Ugab River

Omaruru River

Swakop River

Khan River

Kuiseb River

Orange River

Fish River

Molopo River (South Africa, Botswana)

Nossob River

Hoanib River

Flowing into the Indian Ocean

Zambezi

Kwando River (or Linyanti River or Chobe River)

Flowing into endorheic basins

Etosha Pan

Ekuma River

Oshigambo River

Okavango Delta

Okavango River

Sossusvlei

Tsauchab

Alphabetic list

Ekuma River

Fish River

Hoanib River

Khan River - Kunene River - Kuiseb River - Kwando River

Nossob River

Okavango River - Omaruru River - Orange River - Oshigambo River

Swakop River

Tsauchab

Ugab River

Geography of Namibia

At 825,418 km2 (318,696 sq mi),[1] Namibia is the world's thirty-fourth largest country (afterVenezuela). After Mongolia, Namibia is the least densely populated country in the world (2.5 inhabitants per square kilometre (6.5 /sq mi)).

The Namibian landscape consists generally of five geographical areas, each with characteristic abiotic conditions and vegetation with some variation within and overlap between them: the Central Plateau, the Namib Desert, the Great Escarpment, the Bushveld, and the Kalahari Desert

Central Plateau[edit

edit source]

The Central Plateau runs from north to south, bordered by the Skeleton Coast to the northwest, the Namib Desert and its coastal plains to the southwest, the Orange River to the south, and the Kalahari Desert to the east. The Central Plateau is home to the highest point in Namibia at Königstein elevation 2,606 metres (8,550 ft).[2] Within the wide, flat Central Plateau is the majority of Namibia’s population and economic activity. Windhoek, the nation’s capital, is located here, as well as most of the arable land. Although arable land accounts for only 1% of Namibia, nearly half of the population is employed in agriculture.[3]

The abiotic conditions here are similar to those found along the Escarpment; however the topographic complexity is reduced. Summer temperatures in the area can reach 40 °C (104 °F), and frosts are common in the winter.

Namib Desert[edit]

The Namib Desert is a broad expanse of hyper-arid gravel plains and dunes that stretches along the entire coastline, which varies in width between 100 to many hundreds of kilometres. Areas within the Namib include the Skeleton Coast and the Kaokoveld in the north and the extensive Namib Sand Sea along the central coast.[4] The sands that make up the sand sea are a consequence of erosional processes that take place within the Orange River valley and areas further to the south. As sand-laden waters drop their suspended loads into the Atlantic, onshore currents deposit them along the shore. The prevailing south west winds then pick up and redeposit the sand in the form of massive dunes in the widespread sand sea, the largest sand dunes in the world. In areas where the supply of sand is reduced because of the inability of the sand to cross riverbeds, the winds also scour the land to form large gravel plains. In many areas within the Namib Desert, there is little vegetation with the exception of lichens found in the gravel plains, and in dry river beds where plants can access subterranean water.

Great Escarpment[edit]

The Great Escarpment swiftly rises to over 2,000 metres (6,562 ft). Average temperatures and temperature ranges increase as you move further inland from the cold Atlantic waters, while the lingering coastal fogs slowly diminish. Although the area is rocky with poorly developed soils, it is nonetheless significantly more productive than the Namib Desert. As summer winds are forced over the Escarpment, moisture is extracted as precipitation.[5] The water, along with rapidly changing topography, is responsible for the creation of microhabitats which offer a wide range of organisms, many of them endemic. Vegetation along the escarpment varies in both form and density, with community structure ranging from dense woodlands to more shrubby areas with scattered trees. A number of Acacia species are found here, as well as grasses and other shrubby vegetation.

Bushveld[edit]

The Bushveld is found in north eastern Namibia along the Angolan border and in the Caprivi Strip which is the vestige of a narrow corridor demarcated for the German Empire to access the Zambezi River. The area receives a significantly greater amount of precipitation than the rest of the country, averaging around 400 mm (15.7 in) per year. Temperatures are also cooler and more moderate, with approximate seasonal variations of between 10 and 30 °C (50 and 86 °F). The area is generally flat and the soils sandy, limiting their ability to retain water.[6] Located adjacent to the Bushveld in north-central Namibia is one of nature’s most spectacular features: the Etosha Pan. For most of the year it is a dry, saline wasteland, but during the wet season, it forms a shallow lake covering more than 6,000 square kilometres (2,317 sq mi). The area is ecologically important and vital to the huge numbers of birds and animals from the surrounding savannah that gather in the region as summer drought forces them to the scattered waterholes that ring the pan. The Bushveld area has been demarcated by the World Wildlife Fund as part of the Angolan Mopane woodlands ecoregion, which extends north across the Cunene River into neighbouring Angola.

Kalahari Desert[edit]

The Kalahari Desert is perhaps Namibia’s best known geographical feature. Shared with South Africa and Botswana, it has a variety of localised environments ranging from hyper-arid sandy desert, to areas that seem to defy the common definition of desert. One of these areas, known as the Succulent Karoo, is home to over 5,000 species of plants, nearly half of them endemic; fully one third of the world’s succulents are found in the Karoo.

The reason behind this high productivity and endemism may be the relatively stable nature of precipitation.[7] The Karoo apparently does not experience drought on a regular basis, so even though the area is technically desert, regular winter rains provide enough moisture to support the region’s interesting plant community. Another feature of the Kalahari, indeed many parts of Namibia, are inselbergs, isolated mountains that create microclimates and habitat for organisms not adapted to life in the surrounding desert matrix.

Coastal Desert[edit]

Namibia’s Coastal Desert is one of the oldest deserts in the world. Its sand dunes, created by the strong onshore winds, are the highest in the world.[8]

The Namib Desert and the Namib-Naukluft National Park is located here. The Namibian coastal deserts are the richest source of diamonds on earth, making Namibia the world's largest producer of diamonds. It is divided into the northern Skeleton Coast and the southern Diamond Coast. Because of the location of the shoreline—at the point where the Atlantic's cold water reach Africa—there is often extremely dense fog.[9]

The Namib Desert and the Namib-Naukluft National Park is located here. The Namibian coastal deserts are the richest source of diamonds on earth, making Namibia the world's largest producer of diamonds. It is divided into the northern Skeleton Coast and the southern Diamond Coast. Because of the location of the shoreline—at the point where the Atlantic's cold water reach Africa—there is often extremely dense fog.[9]

Sandy beach comprises 54% and mixed sand and rock add another 28%. Only 16% of the total length is rocky shoreline. The coastal plains are dune fields, gravel plains covered with lichen and some scattered salt pans. Near the coast there are areas where the dunes are vegetated with hammocks.[10] Namibia has rich coastal and marine resources that remain largely unexplored.

The Namibian landscape consists generally of five geographical areas, each with characteristic abiotic conditions and vegetation with some variation within and overlap between them: the Central Plateau, the Namib Desert, the Great Escarpment, the Bushveld, and the Kalahari Desert

Central Plateau[edit

edit source]

The Central Plateau runs from north to south, bordered by the Skeleton Coast to the northwest, the Namib Desert and its coastal plains to the southwest, the Orange River to the south, and the Kalahari Desert to the east. The Central Plateau is home to the highest point in Namibia at Königstein elevation 2,606 metres (8,550 ft).[2] Within the wide, flat Central Plateau is the majority of Namibia’s population and economic activity. Windhoek, the nation’s capital, is located here, as well as most of the arable land. Although arable land accounts for only 1% of Namibia, nearly half of the population is employed in agriculture.[3]

The abiotic conditions here are similar to those found along the Escarpment; however the topographic complexity is reduced. Summer temperatures in the area can reach 40 °C (104 °F), and frosts are common in the winter.

Namib Desert[edit]

The Namib Desert is a broad expanse of hyper-arid gravel plains and dunes that stretches along the entire coastline, which varies in width between 100 to many hundreds of kilometres. Areas within the Namib include the Skeleton Coast and the Kaokoveld in the north and the extensive Namib Sand Sea along the central coast.[4] The sands that make up the sand sea are a consequence of erosional processes that take place within the Orange River valley and areas further to the south. As sand-laden waters drop their suspended loads into the Atlantic, onshore currents deposit them along the shore. The prevailing south west winds then pick up and redeposit the sand in the form of massive dunes in the widespread sand sea, the largest sand dunes in the world. In areas where the supply of sand is reduced because of the inability of the sand to cross riverbeds, the winds also scour the land to form large gravel plains. In many areas within the Namib Desert, there is little vegetation with the exception of lichens found in the gravel plains, and in dry river beds where plants can access subterranean water.

Great Escarpment[edit]

The Great Escarpment swiftly rises to over 2,000 metres (6,562 ft). Average temperatures and temperature ranges increase as you move further inland from the cold Atlantic waters, while the lingering coastal fogs slowly diminish. Although the area is rocky with poorly developed soils, it is nonetheless significantly more productive than the Namib Desert. As summer winds are forced over the Escarpment, moisture is extracted as precipitation.[5] The water, along with rapidly changing topography, is responsible for the creation of microhabitats which offer a wide range of organisms, many of them endemic. Vegetation along the escarpment varies in both form and density, with community structure ranging from dense woodlands to more shrubby areas with scattered trees. A number of Acacia species are found here, as well as grasses and other shrubby vegetation.

Bushveld[edit]

The Bushveld is found in north eastern Namibia along the Angolan border and in the Caprivi Strip which is the vestige of a narrow corridor demarcated for the German Empire to access the Zambezi River. The area receives a significantly greater amount of precipitation than the rest of the country, averaging around 400 mm (15.7 in) per year. Temperatures are also cooler and more moderate, with approximate seasonal variations of between 10 and 30 °C (50 and 86 °F). The area is generally flat and the soils sandy, limiting their ability to retain water.[6] Located adjacent to the Bushveld in north-central Namibia is one of nature’s most spectacular features: the Etosha Pan. For most of the year it is a dry, saline wasteland, but during the wet season, it forms a shallow lake covering more than 6,000 square kilometres (2,317 sq mi). The area is ecologically important and vital to the huge numbers of birds and animals from the surrounding savannah that gather in the region as summer drought forces them to the scattered waterholes that ring the pan. The Bushveld area has been demarcated by the World Wildlife Fund as part of the Angolan Mopane woodlands ecoregion, which extends north across the Cunene River into neighbouring Angola.

Kalahari Desert[edit]

The Kalahari Desert is perhaps Namibia’s best known geographical feature. Shared with South Africa and Botswana, it has a variety of localised environments ranging from hyper-arid sandy desert, to areas that seem to defy the common definition of desert. One of these areas, known as the Succulent Karoo, is home to over 5,000 species of plants, nearly half of them endemic; fully one third of the world’s succulents are found in the Karoo.

The reason behind this high productivity and endemism may be the relatively stable nature of precipitation.[7] The Karoo apparently does not experience drought on a regular basis, so even though the area is technically desert, regular winter rains provide enough moisture to support the region’s interesting plant community. Another feature of the Kalahari, indeed many parts of Namibia, are inselbergs, isolated mountains that create microclimates and habitat for organisms not adapted to life in the surrounding desert matrix.

Coastal Desert[edit]

Namibia’s Coastal Desert is one of the oldest deserts in the world. Its sand dunes, created by the strong onshore winds, are the highest in the world.[8]

The Namib Desert and the Namib-Naukluft National Park is located here. The Namibian coastal deserts are the richest source of diamonds on earth, making Namibia the world's largest producer of diamonds. It is divided into the northern Skeleton Coast and the southern Diamond Coast. Because of the location of the shoreline—at the point where the Atlantic's cold water reach Africa—there is often extremely dense fog.[9]

The Namib Desert and the Namib-Naukluft National Park is located here. The Namibian coastal deserts are the richest source of diamonds on earth, making Namibia the world's largest producer of diamonds. It is divided into the northern Skeleton Coast and the southern Diamond Coast. Because of the location of the shoreline—at the point where the Atlantic's cold water reach Africa—there is often extremely dense fog.[9]Sandy beach comprises 54% and mixed sand and rock add another 28%. Only 16% of the total length is rocky shoreline. The coastal plains are dune fields, gravel plains covered with lichen and some scattered salt pans. Near the coast there are areas where the dunes are vegetated with hammocks.[10] Namibia has rich coastal and marine resources that remain largely unexplored.

Monday, July 29, 2013

Post Independence of Namibia

Post independence

Namibian government has promoted a policy of national reconciliation and issued an amnesty for those who had fought on either side during the liberation war. The civil war in Angola had a limited impact on Namibians living in the north of the country. In 1998, Namibia Defence Force (NDF) troops were sent to the Democratic Republic of the Congo as part of a Southern African Development Community (SADC) contingent. In August 1999, a secessionist attempt in the northeastern Caprivi region was successfully quashed.

Re-election of Sam Nujoma

Sam Nujoma won the presidential elections of 1994 with 76.34% of the votes. There was only one other candidate, Mishake Muyongo of the DTA.In 1998, with one year until the scheduled presidential election when Sam Nujoma would not be allowed to participate in since he had already served the two terms that the constitution allows, SWAPO amended the constitution, allowing three terms instead of two. They were able to do this since SWAPO had a two-thirds majority in both the National Assembly of Namibia and the National Council, which is the minimum needed to amend the constitution.

Sam Nujoma was reelected as president in 1999, winning the election, that had a 62.1% turnout with 76.82%. Second was Ben Ulenga from the Congress of Democrats (COD), that won 10.49% of the votes.

Ben Ulenga is a former SWAPO member and Deputy Minister of Environment and Tourism, and High Commissioner to the United Kingdom. He left SWAPO and became one of the founding members of COD in 1998, after clashing with his party on several questions. He did not approve of the amendment to the constitution, and criticised Namibia's involvement in Congo.

Nujoma was succeeded as President of Namibia by Hifikepunye Pohamba in 2005.

Land reform

One of SWAPO's policies, that had been formulated long before the party came into power, was land reform. Namibia's colonial and Apartheid past had resulted in a situation where about 20 percent of the population owned about 75 percent of all the land. Land was supposed to be redistributed mostly from the white minority to previously landless communities and ex-combatants. The land reform has been slow, mainly because Namibia's constitution only allows land to be bought from farmers willing to sell. Also, the price of land is very high in Namibia, which further complicates the matter.President Sam Nujoma has been vocal in his support of Zimbabwe and its president Robert Mugabe. During the land crisis in Zimbabwe, where the government confiscated white farmers' land by force, fears rose among the white minority and the western world that the same method would be used in Namibia.

Involvement in conflicts in Angola and DRC

In 1999 Namibia signed a mutual defence pact with its northern neighbour Angola. This affected the Angolan Civil War that had been ongoing since Angola's independence in 1975. Both being leftist movements, SWAPO wanted to support the ruling party MPLA in Angola to fight the rebel movement UNITA, whose stronghold was in southern Angola. The defence pact allowed Angolan troops to use Namibian territory when attacking UNITA.The Angolan civil war resulted in a large number of Angolan refugees coming to Namibia. At its peak in 2001 there were over 30,000 Angolan refugees in Namibia. The calmer situation in Angola has made it possible for many of them to return to their home with the help of UNHCR, and in 2004 only 12,600 remained in Namibia. Most of them reside in the refugee camp Osire north of Windhoek.

Namibia also intervened in the Second Congo War, sending troops in support of the Democratic Republic of Congo's president Laurent-Désiré Kabila.

The Caprivi conflict

The Caprivi conflict was an armed conflict between the Caprivi Liberation Army (CLA), a rebel group working for the secession of the Caprivi Strip, and the Namibian government. It started in 1994 and had its peak in the early hours of 2 August 1999 when CLA launched an attack in Katima Mulilo, the provincial capital of the Caprivi Region. Forces of the Namibian government struck back and arrested a number of alleged CLA supporters. The Caprivi conflict has led to the longest and largest trial in the history of Namibia, the Caprivi treason trial.

Struggle for Independence of Namibia

The struggle for independence

In a 1971 advisory opinion, the International Court of Justice upheld UN authority over Namibia, determining that the South African presence in Namibia was illegal and that South Africa therefore was obliged to withdraw its administration from Namibia immediately. The Court also advised UN member states to refrain from implying legal recognition or assistance to the South African presence.

While previously the contract work force was seen as "primitive" and "lack[ing] political consciousness", the summer 1971/72 saw a general strike of 25% of the entire working population (13,000 people), starting in Windhoek and Walvis Bay and soon spreading to Tsumeb and other mines.

In 1975, South Africa sponsored the Turnhalle Constitutional Conference, which sought an "internal settlement" to Namibia. Excluding SWAPO, the conference mainly included bantustan leaders as well as white Namibian political parties.

International pressure

In 1977, the Western Contact Group (WCG) was formed including Canada, France, West Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States. They launched a joint diplomatic effort to bring an internationally acceptable transition to independence for Namibia. The WCG's efforts led to the presentation in 1978 of Security Council Resolution 435 for settling the Namibian problem. The settlement proposal, as it became known, was worked out after lengthy consultations with South Africa, the front-line states (Angola, Botswana, Mozambique, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe), SWAPO, UN officials, and the Western Contact Group. It called for the holding of elections in Namibia under UN supervision and control, the cessation of all hostile acts by all parties, and restrictions on the activities of South African and Namibian military, paramilitary, and police.South Africa agreed to cooperate in achieving the implementation of Resolution 435. Nonetheless, in December 1978, in defiance of the UN proposal, it unilaterally held elections, which were boycotted by SWAPO and a few other political parties. South Africa continued to administer Namibia through its installed multiracial coalitions and an appointed Administrator-General. Negotiations after 1978 focused on issues such as supervision of elections connected with the implementation of the settlement proposal.

Negotiations and transition

In the period, four UN Commissioners for Namibia were appointed. South Africa refused to recognize any of these United Nations appointees. Nevertheless discussions proceeded with UN Commissioner for Namibia N°2 Martti Ahtisaari who played a key role in getting the Constitutional Principles agreed in 1982 by the front-line states, SWAPO, and the Western Contact Group. This agreement created the framework for Namibia's democratic constitution. The US Government's role as mediator was both critical and disputed throughout the period, one example being the intense efforts in 1984 to obtain withdrawal of the South African Defence Force (SADF) from southern Angola. The so-called "Constructive Engagement" by US diplomatic interests was viewed negatively by those who supported internationally recognised independence, while to others US policy seemed to be aimed more towards restraining Soviet-Cuban influence in Angola and linking that to the issue of Namibian independence. In addition, US moves seemed to encourage the South Africans to delay independence by taking initiatives that would keep the Soviet-Cubans in Angola, such as dominating large tracts of southern Angola militarily while at the same time providing surrogate forces for the Angolan opposition movement, UNITA. From, a Transitional Government of National Unity, backed by South Africa and various ethnic political parties, tried unsuccessfully for recognition by the United Nations. Finally, in 1987 when prospects for Namibian independence seemed to be improving, the fourth UN Commissioner for Namibia Bernt Carlsson was appointed. Upon South Africa's relinquishing control of Namibia, Commissioner Carlsson's role would be to administer the country, formulate its framework constitution, and organize free and fair elections based upon a non-racial universal franchise.In May 1988, a US mediation team – headed by Chester A. Crocker, US Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs – brought negotiators from Angola, Cuba, and South Africa, and observers from the Soviet Union together in London. Intense diplomatic activity characterized the next 7 months, as the parties worked out agreements to bring peace to the region and make possible the implementation of UN Security Council Resolution 435 (UNSCR 435). At the Ronald Reagan/Mikhail Gorbachev summit in Moscow (29 May – 1 June 1988) between leaders of the United States and the Soviet Union, it was decided that Cuban troops would be withdrawn from Angola, and Soviet military aid would cease, as soon as South Africa withdrew from Namibia. Agreements to give effect to these decisions were drawn up for signature in New York in December 1988. Cuba, South Africa, and the People's Republic of Angola agreed to a complete withdrawal of foreign troops from Angola. This agreement, known as the Brazzaville Protocol, established a Joint Monitoring Commission (JMC) with the United States and the Soviet Union as observers. The Tripartite Accord, comprising a bilateral agreement between Cuba and Angola, and a tripartite agreement between Angola, Cuba and South Africa whereby South Africa agreed to hand control of Namibia to the United Nations, were signed at UN headquarters in New York City on 22 December 1988. (UN Commissioner N°4 Bernt Carlsson was not present at the signing ceremony. He was killed on flight Pan Am 103 which exploded over Lockerbie, Scotland on 21 December 1988 en route from London to New York. South African foreign minister, Pik Botha, and an official delegation of 22 had a lucky escape. Their booking on Pan Am 103 was cancelled at the last minute and Pik Botha, together with a smaller delegation, caught the earlier Pan Am 101 flight to New York.)

Within a month of the signing of the New York Accords, South African president P. W. Botha suffered a mild stroke, which prevented him from attending a meeting with Namibian leaders on 20 January 1989. His place was taken by acting president J. Christiaan Heunis. Botha had fully recuperated by 1 April 1989 when implementation of UNSCR 435 officially started and the South African–appointed Administrator-General, Louis Pienaar, began the territory's transition to independence. Former UN Commissioner N°2 and now UN Special Representative Martti Ahtisaari arrived in Windhoek in April 1989 to head the UN Transition Assistance Group's (UNTAG) mission.

The transition got off to a shaky start because, contrary to SWAPO President Sam Nujoma's written assurances to the UN Secretary General to abide by a cease-fire and repatriate only unarmed Namibians, it was alleged that approximately 2,000 armed members of the People's Liberation Army of Namibia (PLAN) SWAPO's military wing, crossed the border from Angola in an apparent attempt to establish a military presence in northern Namibia. UNTAG's Martti Ahtisaari took advice from British Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, who was visiting Southern Africa at the time, and authorized a limited contingent of South African troops to assist the South West African Police in restoring order. A period of intense fighting followed, during which 375 PLAN fighters were killed. At a hastily arranged meeting of the Joint Monitoring Commission in Mount Etjo, a game park outside Otjiwarongo, it was agreed to confine the South African forces to base and return PLAN elements to Angola. While that problem was resolved, minor disturbances in the north continued throughout the transition period.

In October 1989, under orders of the UN Security Council, Pretoria was forced to demobilize some 1,600 members of Koevoet (Afrikaans for crowbar). The Koevoet issue had been one of the most difficult UNTAG faced. This counter-insurgency unit was formed by South Africa after the adoption of UNSCR 435, and was not, therefore, mentioned in the Settlement Proposal or related documents. The UN regarded Koevoet as a paramilitary unit which ought to be disbanded but the unit continued to deploy in the north in armoured and heavily armed convoys. In June 1989, the Special Representative told the Administrator-General that this behavior was totally inconsistent with the settlement proposal, which required the police to be lightly armed. Moreover, the vast majority of the Koevoet personnel were quite unsuited for continued employment in the South-West African Police (SWAPOL). The Security Council, in its resolution of 29 August, therefore demanded the disbanding of Koevoet and dismantling of its command structures. South African foreign minister, Pik Botha, announced on 28 September 1989 that 1,200 ex-Koevoet members would be demobilized with effect from the following day. A further 400 such personnel were demobilized on 30 October. These demobilizations were supervised by UNTAG military monitors.

The 11-month transition period ended relatively smoothly. Political prisoners were granted amnesty, discriminatory legislation was repealed, South Africa withdrew all its forces from Namibia, and some 42,000 refugees returned safely and voluntarily under the auspices of the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Almost 98% of registered voters turned out to elect members of the Constituent Assembly. The elections were held in November 1989 and were certified as free and fair by the UN Special Representative, with SWAPO taking 57% of the vote, just short of the two-thirds necessary to have a free hand in revising the framework constitution that had been formulated not by UN Commissioner Bernt Carlsson but by the South African appointee Louis Pienaar. The opposition Democratic Turnhalle Alliance received 29% of the vote. The Constituent Assembly held its first meeting on 21 November 1989 and resolved unanimously to use the 1982 Constitutional Principles in Namibia's new constitution.

(According to The Guardian of 26 July 1991, Pik Botha told a press conference that the South African government had paid more than £20 million to at least seven political parties in Namibia to oppose SWAPO in the run-up to the 1989 elections. He justified the expenditure on the grounds that South Africa was at war with SWAPO at the time.)

Independence

Sam Nujoma was sworn in as the first President of Namibia watched by Nelson Mandela (who had been released from prison shortly beforehand) and representatives from 147 countries, including 20 heads of state.

On 1 March 1994, the coastal enclave of Walvis Bay and 12 offshore islands were transferred to Namibia by South Africa. This followed three years of bilateral negotiations between the two governments and the establishment of a transitional Joint Administrative Authority (JAA) in November 1992 to administer the 780 km2 (300 sq mi) territory. The peaceful resolution of this territorial dispute was praised by the international community, as it fulfilled the provisions of the UNSCR 432 (1978), which declared Walvis Bay to be an integral part of Namibia.

Sunday, July 28, 2013

History of Namibia

The history of Namibia has passed through several distinct stages from

being colonised in the late nineteenth

century to Namibia's independence on 21 March 1990.

From 1884, Namibia was a German colony: German

South-West Africa. After the First World War, the League

of Nations mandated South Africa to administer the territory. Following World War II, the League of Nations

was dissolved in April 1946 and its successor, the United Nations, instituted a Trusteeship system to bring all

of the former German colonies in Africa under UN control. South Africa objected

arguing that a majority of the territory's people were content with South

African rule.

From 1884, Namibia was a German colony: German

South-West Africa. After the First World War, the League

of Nations mandated South Africa to administer the territory. Following World War II, the League of Nations

was dissolved in April 1946 and its successor, the United Nations, instituted a Trusteeship system to bring all

of the former German colonies in Africa under UN control. South Africa objected

arguing that a majority of the territory's people were content with South

African rule.

Legal argument ensued over the course of the next twenty years until, in

October 1966, the UN General

Assembly decided to end the mandate, declaring that South Africa had no

other right to administer the territory and that henceforth South-West Africa

was to come under the direct responsibility of the UN (Resolution 2145 XXI of 27

October 1966).

Legal argument ensued over the course of the next twenty years until, in

October 1966, the UN General

Assembly decided to end the mandate, declaring that South Africa had no

other right to administer the territory and that henceforth South-West Africa

was to come under the direct responsibility of the UN (Resolution 2145 XXI of 27

October 1966).

With their horses and guns, the Afrikaners proved to be militarily superior and forced the Herero to give them cattle as tribute.

The last group to arrive in Namibia before the Europeans were the Basters – descendants of Boer men and African women (mostly Nama). Being Calvinist and Afrikaans-speaking, they considered themselves to be culturally more "white" than "black". As with the Oorlams, they were forced northwards by the expansion of white settlers when, in 1868, a group of about 90 families crossed the Orange River into Namibia. The Basters settled in central Namibia, where they founded the city Rehoboth. In 1872 they founded the "Free Republic of Rehoboth" and adopted a constitution stating that the nation should be led by a "Kaptein" directly elected by the people, and that there should be a small parliament, or Volkraad, consisting of three directly-elected citizens.

The next European to visit Namibia was also a Portuguese, Bartholomeu Dias, who stopped at what today is Walvis Bay and Lüderitz (which he named Angra Pequena) on his way to round the Cape of Good Hope.

The inhospitable Namib Desert constituted a formidable barrier and neither of the Portuguese explorers went far inland.

In 1793 the Dutch authority in the Cape decided to take control of Walvis bay, since it was the only good deep-water harbour along the Skeleton Coast. When the United Kingdom took control of the Cape Colony in 1797, they also took over Walvis Bay. But white settlement in the area was limited, and neither the Dutch nor the British penetrated far into the country.

One of the first European groups to show interest in Namibia were the missionaries. In 1805 the London Missionary Society began working in Namibia, moving north from the Cape Colony. In 1811 they founded the town Bethanie in southern Namibia, where they built a church, which today is Namibia's oldest building.

In the 1840s the German Rhenish Mission Society started working in Namibia and co-operating with the London Missionary Society. It was not until the 19th century, when European powers sought to carve up the African continent between them in the so-called "Scramble for Africa", that Europeans – Germany and Great Britain in the forefront – became interested in Namibia.

The first territorial claim on a part of Namibia came when Britain occupied Walvis Bay, confirming the settlement of 1797, and permitted the Cape Colony to annex it in 1878. The annexation was an attempt to forestall German ambitions in the area, and it also guaranteed control of the good deepwater harbour on the way to the Cape Colony and other British colonies on Africa's east coast.

In 1883, a German trader, Adolf Lüderitz, bought Angra Pequena from the Nama

chief Joseph

Fredericks. The price he paid was 10,000 marks (ℳ) and 260 guns. He

soon renamed the coastal area after himself, giving it the name Lüderitz.

Believing that Britain was soon about to declare the whole area a protectorate,

Lüderitz advised the German chancellor Otto von Bismarck to claim it. In 1884

Bismarck did so, thereby establishing German

South West Africa as a colony (Deutsch-Südwestafrika in German).

A region, the Caprivi Strip, became a part of German South West Africa after the Heligoland-Zanzibar Treaty on 1 July 1890, between the United Kingdom and Germany. The Caprivi Strip in Namibia gave Germany access to the Zambezi River and thereby to German colonies in East Africa. In exchange for the island of Heligoland in the North Sea, Britain took control of the island of Zanzibar in East Africa.

The Namaqua's resistance proved to be unsuccessful, however, and in 1894 Witbooi was forced to sign a "protection treaty" with the Germans. The treaty allowed the Namaqua to keep their arms, and Witbooi was released having given his word of honour not to continue with the Hottentot uprising.

In 1894 major Theodor Leutwein was appointed governor of German South-West Africa. He tried without great success to apply the principle of "colonialism without bloodshed". The protection treaty did have the effect of stabilising the situation but pockets of rebellion persisted, and were put down by an elite German regiment Schutztruppe, while real peace was never achieved between the colonialists and the natives.

Being the only German colony considered suitable for white settlement at the time, Namibia attracted a large influx of German settlers. In 1903 there were 3,700 Germans living in the area, and by 1910 their number had increased to 13,000. Another reason for German settlement was the discovery of diamonds in 1908. Diamond production continues to be a very important part of Namibia's economy.

The settlers were encouraged by the government to appropriate land from the natives, and forced labour – hard to distinguish from slavery – was used. As a result, relations between the German settlers and the natives deteriorated.

In the beginning of the war the Herero, under the leadership of chief Samuel Maharero had the upper hand. With good knowledge of the terrain they had little problem in defending themselves against the Schutztruppe (initially numbering only 766). Soon the Namaqua people joined the war, again under the leadership of Hendrik Witbooi.

To cope with the situation, Germany sent 14,000 additional troops who soon

crushed the rebellion in the Battle of Waterberg in 1905. Earlier von

Trotha issued an ultimatum to the Herero, denying them citizenship rights and

ordering them to leave the country or be killed. In order to escape, the Herero

retreated into the waterless Omaheke region, a western arm of the Kalahari Desert, where

many of them died of thirst. The German forces guarded every water source and

were given orders to shoot any adult male Herero on sight. Only a few of them

managed to escape into neighbouring British territories. These tragic events,

known as the Herero and Namaqua Genocide, resulted in the death of

between 24,000 and 65,000 Herero (estimated at 50% to 70% of the total Herero

population) and 10,000 Nama (50% of the total Nama population). The genocide was

characterized by widespread death by starvation and from consumption of well

water which had been poisoned by the Germans in the Namib Desert.

Descendants of Lothar von Trotha apologized to six chiefs of Herero royal houses for the actions of their ancestor on 7 October 2007.

In February 1917, Mandume Ya Ndemufayo, the last king of the Kwanyama of Ovamboland, was killed in a joint attack by South African forces for resisting South African sovereignty over his people.

On 17 December 1920, South Africa undertook administration of South-West Africa under the terms of Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations and a Class C Mandate agreement by the League Council. The Class C mandate, supposed to be used for the least developed territories, gave South Africa full power of administration and legislation over the territory, but required that South Africa promote the material and moral well-being and social progress of the people.

Following the League's supersession by the United Nations in 1946, South Africa refused to surrender its earlier mandate to be replaced by a United Nations Trusteeship agreement, requiring closer international monitoring of the territory's administration. Although the South African government wanted to incorporate "South-West Africa" into its territory, it never officially did so, although it was administered as the de facto 'fifth province', with the white minority having representation in the whites-only Parliament of South Africa. In 1959, the colonial forces in Windhoek sought to remove black residents further away from the white area of town. The residents protested and the subsequent killing of eleven protesters spawned by the Namibian War of Independence with the formation of united black opposition to South African rule as well as the township of Katutura.

During the 1960s, as the European powers granted independence to their colonies and trust territories in Africa, pressure mounted on South Africa to do so in Namibia, which was then South-West Africa. On the dismissal (1966) by the International Court of Justice of a complaint brought by Ethiopia and Liberia against South Africa's continued presence in the territory, the U.N. General Assembly revoked South Africa's mandate.

From 1884, Namibia was a German colony: German

South-West Africa. After the First World War, the League

of Nations mandated South Africa to administer the territory. Following World War II, the League of Nations

was dissolved in April 1946 and its successor, the United Nations, instituted a Trusteeship system to bring all

of the former German colonies in Africa under UN control. South Africa objected

arguing that a majority of the territory's people were content with South

African rule.

From 1884, Namibia was a German colony: German

South-West Africa. After the First World War, the League

of Nations mandated South Africa to administer the territory. Following World War II, the League of Nations

was dissolved in April 1946 and its successor, the United Nations, instituted a Trusteeship system to bring all

of the former German colonies in Africa under UN control. South Africa objected

arguing that a majority of the territory's people were content with South

African rule. Legal argument ensued over the course of the next twenty years until, in

October 1966, the UN General

Assembly decided to end the mandate, declaring that South Africa had no

other right to administer the territory and that henceforth South-West Africa

was to come under the direct responsibility of the UN (Resolution 2145 XXI of 27

October 1966).

Legal argument ensued over the course of the next twenty years until, in

October 1966, the UN General

Assembly decided to end the mandate, declaring that South Africa had no

other right to administer the territory and that henceforth South-West Africa

was to come under the direct responsibility of the UN (Resolution 2145 XXI of 27

October 1966).Bantu immigration - the Herero

During the 17th century the Herero, a pastoral, nomadic people keeping cattle, moved into Namibia. They came from the east African lakes and entered Namibia from the northwest. First they resided in Kaokoland, but in the middle of the 19th century some tribes moved further south and into Damaraland. A number of tribes remained in Kaokoland: these were the Himba people, who are still there today. The Herero were said to have enslaved certain groups and displaced others such as the Bushmen to marginal areas unsuitable for their way of life.The Oorlams

In the 19th century white farmers, mostly Boers moved farther northwards pushing the indigenous Khoisan peoples, who put up a fierce resistance, across the Orange River. Known as Oorlams, these Khoisan adopted Boer customs and spoke a language similar to Afrikaans. Armed with guns, the Oorlams caused instability as more and more came to settle in Namaqualand and eventually conflict arose between them and the Nama. Under the leadership of Jonker Afrikaner, the Oorlams used their superior weapons to take control of the best grazing land. In the 1830s Jonker Afrikaner concluded an agreement with the Nama chief Oaseb whereby the Oorlams would protect the central grasslands of Namibia from the Herero who were then pushing southwards. In return Jonker Afrikaner was recognised as overlord, received tribute from the Nama and settled at what today is Windhoek, on the borders of Herero territory. The Afrikaners soon came in conflict with the Herero who entered Damaraland from the south at about the same time as the Afrikaner started to expand farther north from Namaqualand. Both the Herero and the Afrikaner wanted to use the grasslands of Damaraland for their herds. This resulted in warfare between the Herero and the Oorlams as well as between the two of them and the Damara, who were the original inhabitants of the area. The Damara were displaced by the fighting and many were killed.With their horses and guns, the Afrikaners proved to be militarily superior and forced the Herero to give them cattle as tribute.

Baster immigration

The last group to arrive in Namibia before the Europeans were the Basters – descendants of Boer men and African women (mostly Nama). Being Calvinist and Afrikaans-speaking, they considered themselves to be culturally more "white" than "black". As with the Oorlams, they were forced northwards by the expansion of white settlers when, in 1868, a group of about 90 families crossed the Orange River into Namibia. The Basters settled in central Namibia, where they founded the city Rehoboth. In 1872 they founded the "Free Republic of Rehoboth" and adopted a constitution stating that the nation should be led by a "Kaptein" directly elected by the people, and that there should be a small parliament, or Volkraad, consisting of three directly-elected citizens.

European influence and colonisation

The first European to set foot on Namibian soil was the Portuguese Diogo Cão in 1485, who stopped briefly on the Skeleton Coast, and raised a limestone cross there, on his exploratory mission along the west coast of Africa.The next European to visit Namibia was also a Portuguese, Bartholomeu Dias, who stopped at what today is Walvis Bay and Lüderitz (which he named Angra Pequena) on his way to round the Cape of Good Hope.

The inhospitable Namib Desert constituted a formidable barrier and neither of the Portuguese explorers went far inland.

In 1793 the Dutch authority in the Cape decided to take control of Walvis bay, since it was the only good deep-water harbour along the Skeleton Coast. When the United Kingdom took control of the Cape Colony in 1797, they also took over Walvis Bay. But white settlement in the area was limited, and neither the Dutch nor the British penetrated far into the country.

One of the first European groups to show interest in Namibia were the missionaries. In 1805 the London Missionary Society began working in Namibia, moving north from the Cape Colony. In 1811 they founded the town Bethanie in southern Namibia, where they built a church, which today is Namibia's oldest building.

In the 1840s the German Rhenish Mission Society started working in Namibia and co-operating with the London Missionary Society. It was not until the 19th century, when European powers sought to carve up the African continent between them in the so-called "Scramble for Africa", that Europeans – Germany and Great Britain in the forefront – became interested in Namibia.

The first territorial claim on a part of Namibia came when Britain occupied Walvis Bay, confirming the settlement of 1797, and permitted the Cape Colony to annex it in 1878. The annexation was an attempt to forestall German ambitions in the area, and it also guaranteed control of the good deepwater harbour on the way to the Cape Colony and other British colonies on Africa's east coast.

A region, the Caprivi Strip, became a part of German South West Africa after the Heligoland-Zanzibar Treaty on 1 July 1890, between the United Kingdom and Germany. The Caprivi Strip in Namibia gave Germany access to the Zambezi River and thereby to German colonies in East Africa. In exchange for the island of Heligoland in the North Sea, Britain took control of the island of Zanzibar in East Africa.

German South-West Africa

Soon after declaring Lüderitz and a vast area along the atlantic coast a German protectorate, German troops were deployed as conflicts with the native tribes flared up, most significantly with the Namaqua. Under the leadership of the tribal chief Hendrik Witbooi, the Namaqua put up a fierce resistance to the German occupation. Contemporary media called the conflict "The Hottentot Uprising".The Namaqua's resistance proved to be unsuccessful, however, and in 1894 Witbooi was forced to sign a "protection treaty" with the Germans. The treaty allowed the Namaqua to keep their arms, and Witbooi was released having given his word of honour not to continue with the Hottentot uprising.

In 1894 major Theodor Leutwein was appointed governor of German South-West Africa. He tried without great success to apply the principle of "colonialism without bloodshed". The protection treaty did have the effect of stabilising the situation but pockets of rebellion persisted, and were put down by an elite German regiment Schutztruppe, while real peace was never achieved between the colonialists and the natives.

Being the only German colony considered suitable for white settlement at the time, Namibia attracted a large influx of German settlers. In 1903 there were 3,700 Germans living in the area, and by 1910 their number had increased to 13,000. Another reason for German settlement was the discovery of diamonds in 1908. Diamond production continues to be a very important part of Namibia's economy.

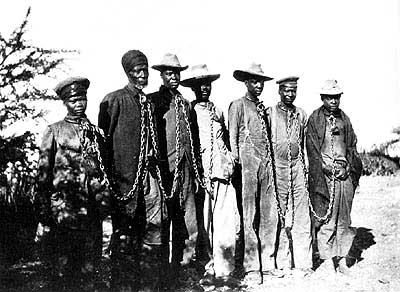

The settlers were encouraged by the government to appropriate land from the natives, and forced labour – hard to distinguish from slavery – was used. As a result, relations between the German settlers and the natives deteriorated.

The Herero and Namaqua wars

The ongoing local rebellions escalated in 1904 into the Herero and Namaqua Wars when the Herero attacked remote farms on the countryside, killing approximately 150 Germans.

The outbreak of rebellion was considered to be a result of Theodor Leutwein's softer tactics, and he was replaced by the more notorious General Lothar von Trotha.In the beginning of the war the Herero, under the leadership of chief Samuel Maharero had the upper hand. With good knowledge of the terrain they had little problem in defending themselves against the Schutztruppe (initially numbering only 766). Soon the Namaqua people joined the war, again under the leadership of Hendrik Witbooi.

Descendants of Lothar von Trotha apologized to six chiefs of Herero royal houses for the actions of their ancestor on 7 October 2007.

South African rule

In 1915, during World War I, South Africa, being a member of the British Commonwealth and a former British colony, occupied the German colony of South-West Africa.In February 1917, Mandume Ya Ndemufayo, the last king of the Kwanyama of Ovamboland, was killed in a joint attack by South African forces for resisting South African sovereignty over his people.

On 17 December 1920, South Africa undertook administration of South-West Africa under the terms of Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations and a Class C Mandate agreement by the League Council. The Class C mandate, supposed to be used for the least developed territories, gave South Africa full power of administration and legislation over the territory, but required that South Africa promote the material and moral well-being and social progress of the people.

Following the League's supersession by the United Nations in 1946, South Africa refused to surrender its earlier mandate to be replaced by a United Nations Trusteeship agreement, requiring closer international monitoring of the territory's administration. Although the South African government wanted to incorporate "South-West Africa" into its territory, it never officially did so, although it was administered as the de facto 'fifth province', with the white minority having representation in the whites-only Parliament of South Africa. In 1959, the colonial forces in Windhoek sought to remove black residents further away from the white area of town. The residents protested and the subsequent killing of eleven protesters spawned by the Namibian War of Independence with the formation of united black opposition to South African rule as well as the township of Katutura.

During the 1960s, as the European powers granted independence to their colonies and trust territories in Africa, pressure mounted on South Africa to do so in Namibia, which was then South-West Africa. On the dismissal (1966) by the International Court of Justice of a complaint brought by Ethiopia and Liberia against South Africa's continued presence in the territory, the U.N. General Assembly revoked South Africa's mandate.